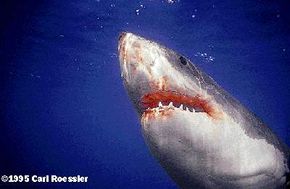

Sharks strike terror into the hearts of people around the world like no other creatures. Their fearsome appearance, large size, and hostile, alien environment combine to make them seem like something straight out of a nightmare. The sudden violence of a shark attack is truly a terrifying experience for the victim -- but are sharks really man-eating monsters with a taste for human flesh?

In this article, we'll find out why sharks attack, what an attack is like, and what kinds of sharks attack people most often. We'll also look at some ways to avoid shark attacks.

Advertisement

Why Sharks Attack

Ninety percent or more of shark incidents are mistakes. They assume that we're something that we are not.- Gary Adkison, diver ("Sharkbite! Surviving the Great White")

Although shark attacks can seem vicious and brutal, it's important to remember that sharks aren't evil creatures constantly on the lookout for humans to attack. They are animals obeying their instincts, like all other animals. As predators at the top of the ocean food chain, sharks are designed to hunt and eat large amounts of meat. A shark's diet consists of other sea creatures -- mainly fish, sea turtles, whales and sea lions and seals. Humans are not on the menu. In fact, humans don't provide enough high-fat meat for sharks, which need a lot of energy to power their large, muscular bodies.

If sharks aren't interested in eating humans, why do they attack us? The first clue comes in the pattern that most shark attacks take. In the majority of recorded attacks, the shark bites the victim, hangs on for a few seconds (possibly dragging the victim through the water or under the surface), and then lets go. It is very rare for a shark to make repeated attacks and actually feed on a human victim. The shark is simply mistaking a human for something it usually eats. Once the shark gets a taste, it realizes that this isn't its usual food, and it lets go.

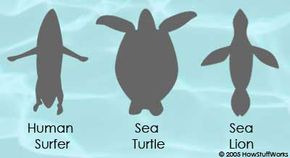

The shark's confusion is easier to understand once we start to look at things from the shark's point of view. Many attack victims are surfers or people riding boogie boards. A shark swimming below sees a roughly oval shape with arms and legs dangling off, paddling along. This bears a close resemblance to a sea lion (the main prey of great white sharks) or a sea turtle (a common food for tiger sharks).

Advertisement