We tend to think of Antarctica as being a giant, frozen, empty wasteland. If that's the impression you personally have of the continent at the south end of our planet ... congratulations! It is indeed just as huge, frozen and full of a whole lot of nothing as you think it is.

This said, like in all deserts, people do live and work there. In the case of the southernmost continent, the humans there mostly comprise polar researchers trying to figure out what Antarctica's deal is, and the drivers, mechanics, cooks, pilots and electricians who support them and keep the research stations running.

Advertisement

So, what's it like living and working on the most remote place on the planet?

1. There are a few different ways to live and work in Antarctica.

Antarctica's home to 75 individual research stations, and they're run by 30 countries. Of these science bases, 45 are actively operating year-round — although most are accessible for only a three-month window every year due to weather conditions. Researchers first have their stuff shipped to a base like the U.S. McMurdo Station on Ross Island, which they use as a staging area for their field expedition. Once they're ready for the field, they're taken with all their stuff in a plane and dropped off.

Some researchers work on ships, but not all ships are research vessels. During the austral summer, cruise ships regularly depart from Argentina and travel to the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, which is considered the Banana Belt of Antarctica — it's much warmer than the rest of the continent and it's where virtually all the wildlife hangs out.

2. For such a lonely place, you're rarely alone.

Pretty much everybody on Antarctica lives in cramped quarters — either in tents or in dormitories or on ships.

"It's tough not getting any alone time for many weeks at a time," says Dr. Nerida Wilson, an invertebrate marine molecular biologist at the Western Australian Museum, via email. "I've always been based on ships, where the work hours are long and the sleeping quarters are close — often four in a very small bunk room. Being alone requires a) having the time, and b) having a place to go. Because of safety, you can't always roam the decks of the ship alone, so mostly you are in company."

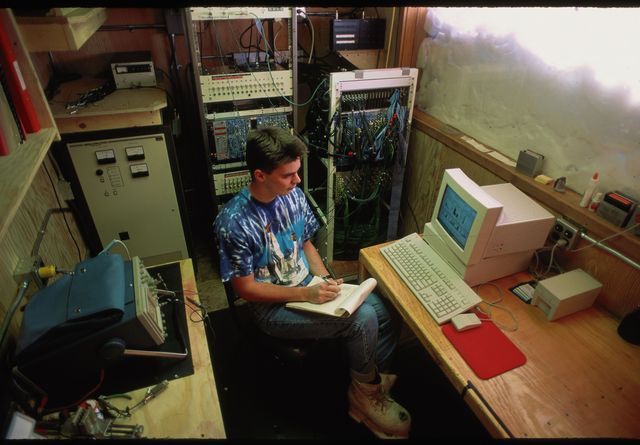

3. The research stations are like small towns — but only kind of.

Very few people overwinter in Antarctica, and the continent has no indigenous population, so nobody was born there, there are no children around, nobody has much of a history there.

"An Antarctic research station is like a remote mining town, but because it's nobody's permanent home, it's everybody's home," says Dr. Jenny Baeseman, a polar researcher and the executive director of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR). "Everybody's very friendly and helpful. Everyone feels excited and fortunate to be there."

Because there is 24-hour daylight during the austral summer, the temporary residents work a lot, but in their free time they hang out at the bar or the coffee shop, go to a movie, play trivia. Sadly, the bowling alley the U.S. Navy built at McMurdo in the 1960s closed in 2009.

4. The weather can "turn to milk in five minutes."

Dr. David Dallmeyer, professor emeritus in the University of Georgia's geology department, spent 20 years as a naturalist on small Antarctic cruise ships. He also spent a few field seasons out on the ice as well studying the geology of the area:

"My first day in the field, we got dropped off 600 miles inland from McMurdo," he says. "We watched the plane turn into a little speck in the distance, and we started to our field site. Pretty soon the wind came up, a thick fog developed, and all of a sudden I realized we were walking over our own tracks — we were walking in circles. We shut it down, put up the emergency tents and we sat there for two and a half days. I'd say the wind was easily 50 knots."

5. You might need to send the contents of your outhouse back to your homeland.

Depending where your field work is, you might be permitted to cut a toilet in the ice, but Baeseman's team, whose field research was in the McMurdo Dry Valleys — part of the protected 2 percent of the continent not covered in snow and ice (it has been millions of years since the last rainfall) — had to ship all of its human waste back to the United States.

"You can't pee on the ground, and you have to separate the pee and poop into different buckets," she says. "That's easier for men than for women, obviously."

6. There are no smells.

With the exception of the other humans you're almost constantly around, almost nothing on Antarctica smells. There are no plants or animals to stink up the place.

"When you're coming back on the plane from McMurdo to New Zealand, about three quarters of the way back, you can start smelling plants," says Baeseman. "Your sense of smell is so desensitized that the smell of pollen in the air just washes over you. It's incredible."

Advertisement