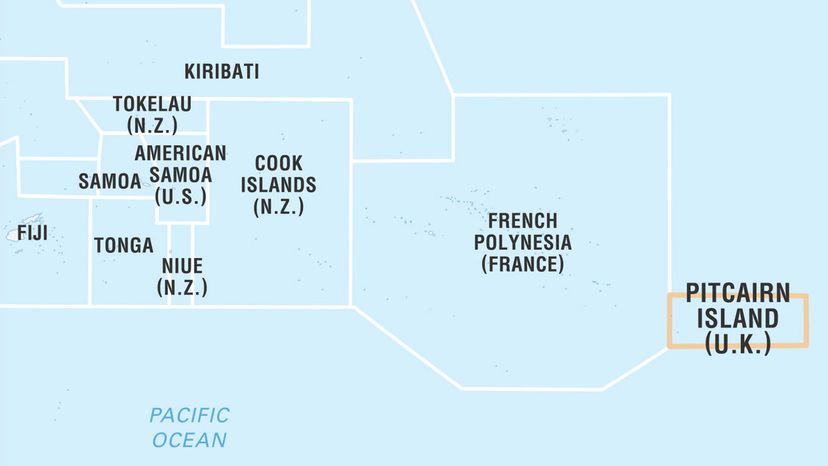

The story seems quite implausible. In 1789, several sailors led by Fletcher Christian seized control of the HMS Bounty, then set Capt. William Bligh and his supporters adrift in the South Pacific sea. (The story was told in the movies "Mutiny on the Bounty" and "The Bounty.") Fearing prosecution if they settled in a local community, the British mutineers spent several months scoping out remote locales, picking up 19 Tahitian companions along the way. Eventually, the group decided to make their new home on a deserted volcanic island they'd discovered some 1,350 miles (2,170 kilometers) southeast of Tahiti. Today, against all odds, their descendants still live on that same subtropical island, Pitcairn.

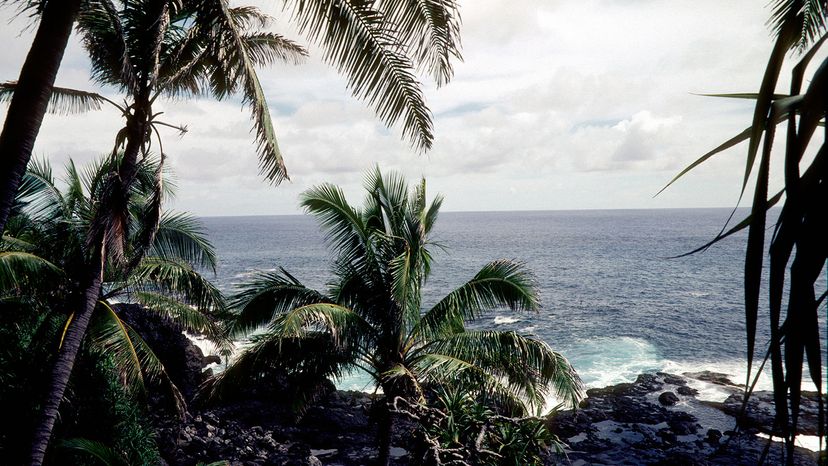

Pitcairn is part of the four Pitcairn Islands, a British Overseas Territory considered one of the world's most remote inhabited islands. The other islands in the group, all uninhabited, are Ducie, Henderson and Oeno. Pitcairn is small — just 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) long and 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) wide. It's also rugged, with steep cliffs and no easy way for boats to dock. In fact, visiting ships still drop anchor several hundred yards from Bounty Bay, then are met by residents steering longboats.

Advertisement

Despite being settled for more than 200 years, Pitcairn's population hasn't changed much. While it reached a peak of 233 in 1937, today the island is home to just 50 or so residents, not many more than when the mutineers first arrived.

With limited acreage and few residents, amenities on the island are minimal. There's a general store, health clinic, post office, museum, library, treasury and tourism center, plus Pulau School, which educates kids through primary school. (Currently, it has just three students.) After that, children typically receive their higher education at boarding school in New Zealand.

Since there's no airport on the island, residents are linked to the outside world mainly via a passenger/cargo ship, the MV Silver Supporter, that travels between French Polynesia and Pitcairn on a limited basis. The trip requires spending at least two nights at sea and there are just 12 visitor berths. The ship comes about once a month.

Interestingly, most native Pitkerners are Seventh-Day Adventists. Originally followers of the Church of England, the mutineers' religion, the group was converted in 1887 by an Adventist missionary and the only church on the island is a Seventh-day Adventist church.

Advertisement