Do you ever dream of flying -- making lazy circles in the sky like a seagull or a hawk? If you do, you're not alone. Dreaming of flying is quite common, and if you believe dream analysis, it's a sign of good things to come. It means you're on top of a particular situation and that you're enjoying a sense of power and freedom [source: Dream Moods].

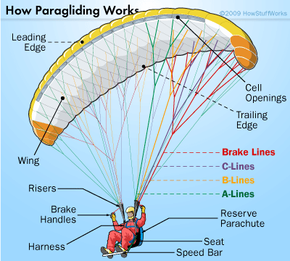

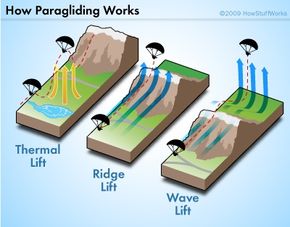

But you don't have to leave flying to your dreams. You can do it while you're awake. We're not talking about flying in an airplane or a hot air balloon. We're talking about paragliding -- nonmotorized, foot-launched flying with an inflatable wing. Enthusiasts call it the simplest form of human flight. Using air currents and shifting their own body weight, paragliders can fly to heights of 23,000 feet (7,000 meters) with their paragliding sails. You can't beat the view, and paragliders find the solitude incredibly peaceful.

Advertisement

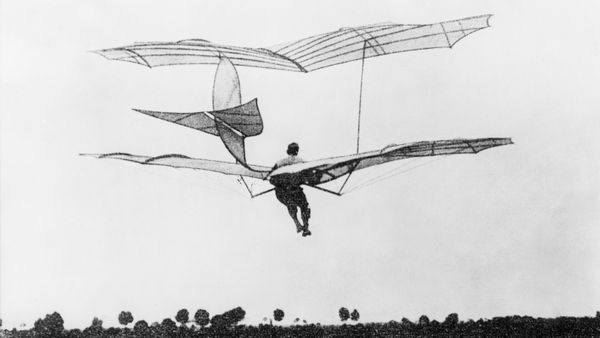

In theory, paragliding is similar to hang gliding. But there are several important differences. Hang gliders typically have an aluminum frame with a V-shaped wing. Paragliders have no frame, and the wing is an elliptical-shaped parachute that folds up to the size of a backpack when it's not being used. These features make paragliders considerably lighter and more convenient to transport than hang gliders.

Paragliders also soar a bit more slowly than hang gliders, which makes it easier for people to learn to fly them. You might think paragliding is like parachuting. But there's one main difference. Paragliding pilots start on the ground with their parachutes already deployed, and the wind takes them up into the sky. Parachuters fall from the sky and deploy the parachute as they get closer to the ground.

What else makes paragliding stand apart? And when was this way of flying invented?

Advertisement