The basic idea behind surfing has been around for thousands of years. It probably started when Polynesian fishermen discovered that catching a wave was a speedy way to get to shore. In Hawaii, surfing gradually became a sport and an expression of social status -- the longer the surfboard, the more important the surfer's role in the community.

When missionaries and colonists arrived in Hawaii in the 1700s, surfing's reputation soured. Some newcomers were offended by the idea of scantily-dressed men and women surfing together. Missionaries banned the sport, and the islands' native population declined in the face of an influx of colonists. As a result, the practice of surfing dwindled until the 1900s, when surfers like George Freeth and Duke Kahanamoku caught the eye of the public and the media. This sparked resurgence in surfing as a recreational activity.

Advertisement

As surfing grew in popularity, it changed dramatically. Hawaiian surfboards had been 10 to 16 feet (3 to 4.9 meters) long and made from solid wood. They could carry a person from the breakers to the shore, but they were heavy and hard to steer. Twentieth-century surfers made improvements to surfboards that allowed riders to control how and where they moved on the waves. New materials made boards lighter and easier to manage while fins and new board shapes added stability and maneuverability. Instead of simply aiming a board at the shore and trying to stay afloat, surfers could rapidly change direction, position themselves precisely on a crashing wave and even launch themselves from a wave's crest.

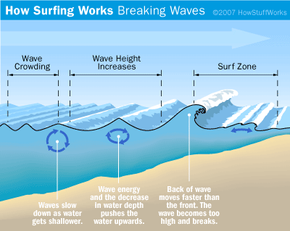

The ability to balance and maneuver on rapidly-moving water is pretty amazing, but it's not the only incredible thing about surfing. There are some specific requirements for good surf conditions, and these conditions exist only along the world's coastlines. Artificially constructing waves or changing the way natural waves break is difficult or even impossible -- in other words, you can only surf where the good waves are. In spite of this limitation, surfing has spawned a musical genre, multiple films, a wealth of slang terms and an entire culture.

One reason behind surfing's popularity is that it doesn't take a lot of gear to get started. We'll look at surfboards in the next section.

Advertisement