You can't just head outside, poke around some rocks and hope to find specific types of gems and crystals. Compare gem hunting to bird watching -- if you want to spot a certain species of bird, you wouldn't aimlessly wander around a forest. You'd learn where that bird lives, what trees it nests in, what it eats, and what its migration patterns are -- leading you to make its eventual discovery.

Let's say you want to find some malachite specimens to add to your gem collection. This mineral is often found near limestone and copper deposits and, within the United States, is most often found in Arizona [source: diamond. Because diamonds are created under extreme pressure, they form deep within the Earth. They're most common in areas where deep mantle rocks have been pushed to the surface by geological processes. They can also be found in the alluvial deposits (rocks and soil deposited by water) along rivers that flow from these areas.

Minerals formed in Earth's mantle can find their way to the surface over the span of millions of years due to huge geologic effects such as tectonic plate upheaval. Earthquakes and volcanoes can bring deep rocks to the surface, while wind or water erosion gradually wears down surface soils to reveal buried bedrock. Humans can reveal bedrock as well, which is why it can be very rewarding to hunt for gems near tunnels, railroads or construction sites (if you're allowed).

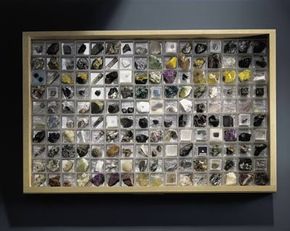

There are numerous gem and mineral guidebooks available, many of them designed to fit in a pocket or backpack. These guidebooks can help you distinguish and identify specimens, especially because the rough forms of gems look very different from the gleaming jewels we typically imagine. In rough form, gems are partly or wholly encased in other material, usually rock. They may resemble translucent lumps or have a more defined shape, depending on the crystalline structure of the mineral. If possible, bring experienced gem hunters along on your first trip. They'll know how to spot certain minerals, and their knowledge will go beyond what you can learn from a book. You could also learn more by visiting a local museum that features samples common to the region.

For every gem in the world, there's a different way to find it. Australian sapphires are found in a certain region covered with alluvial deposits. They're strewn throughout a gravel layer beneath the topsoil. Gem hunters dig through the gravel layer and filter the rocks by putting them in a pan and shaking them in water. Because sapphires are heavier than most rocks, they tend to settle to the bottom of the pan. When the pan is flipped over and emptied, any sapphires will be sitting on top.

Panning for gold also relies on the weight of the mineral. Flakes and pellets of gold can be found mixed with gravel and sediments. Gold is heavier than water, so shaking a pan full of dirt, rock and water settles any gold to the bottom. The other material can be washed over the side, leaving the gold behind. Sluices are long channels (like miniature waterslides) with ridges on the bottom. Large volumes of dirt, rock and water course down the sluice, leaving heavy gold caught in the ridges.

There are tens of thousands of types of minerals in existence. And even though the varieties we would call gems are fewer, they're created under combinations of conditions so vast as to be nearly infinite. Pressure, heat, location, the presence of other minerals and impurities, water, and geologic forces exerted later all contribute to the hardness, clarity, crystalline structure and color of gems and minerals. That's what makes them so rare.

You'll need a lot more than a guidebook to discover hidden treasures and buried jewels. Find out what gear you should bring in the next section.