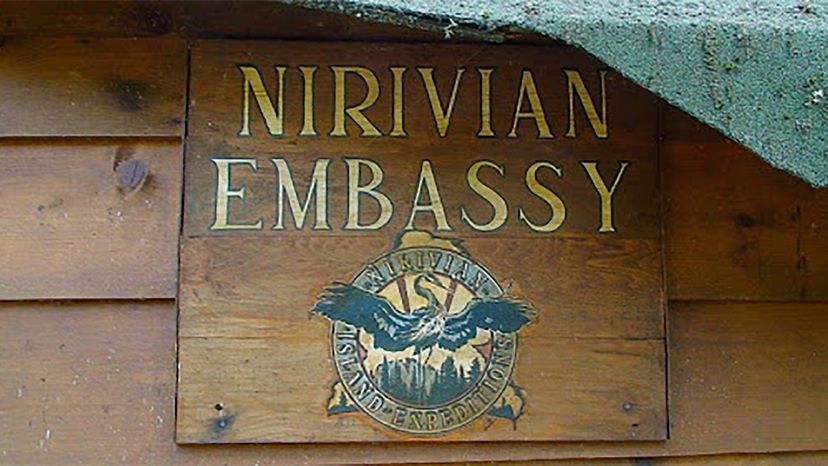

Among the world's numerous micronations — generally, tiny realms tucked into nooks and crannies on the map, where someone has proclaimed sovereignty that's not recognized by the rest of the world — the Republic of Nirivia stands apart. It might be the only country in the world that was founded around a campfire, by a group of outdoorsy, whiskey-drinking Canadians who gave themselves fancy titles in jest, and mostly seem to have wanted to make a point about the importance of preserving a pristine natural area from logging and mining.

Nirivia comprises 59 islands situated on the northern part of Lake Superior, the biggest of which is St. Ignace Island. It's the sort of place that's a paradise for hikers and kayakers — full of verdant woods, sea caves, beaches and striking columnar basalt formations, home to an assortment of aquatic and avian creatures. It's a locale whose spectacular scenery has been compared to Norway.

Advertisement

It was a place treasured by a group of friends who'd grown up in the area and spent their youth exploring its wonders. In a 2014 article by Charles Wilkins in Cottage Life magazine, one of Nirivia's founding fathers, Rusty Evans, explained that they seized upon a perceived loophole in a land claim filed by native people, under a 19th century treaty with the Canadian government. That claim was for a stretch of land along Lake Superior's north shore, but Nirivia's founders noticed that it didn't include the islands. Evans took that to mean that the natives hadn't ceded the islands to Canada in the first place, leaving their status murky.

"We oughta just swipe them from the government — declare our own country!" Evans recalled telling his friends, as recounted in the Cottage Life article.

They even came up with a name — Nirivia. "It was like Nirvana, but they had a little booze in them," explains Zack Kruzins, the owner of Such a Nice Day Adventures, an outdoor adventure and education company based in northwestern Ontario. (He's also co-author of "A Paddler's Guide to the Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area.")

"They started this place, which is more like a state of mind. It's a pristine, beautiful wild place that's so far from everything that it seems like a separate country," Kruzins explains. "It's got this energy that's magical."

Advertisement