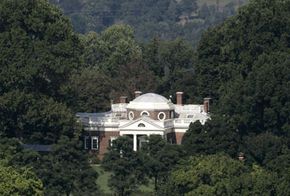

Centuries before Bill Gates built his multimillion-dollar smart house, Thomas Jefferson designed his home, Monticello. Like the Gates mansion, where home networking technology simplifies and streamlines daily tasks, Jefferson engineered Monticello "with a greater eye to convenience."

The name "Monticello" is Italian and means "little hill" [source: vineyards, gardens and workshops. The house is more than an architectural wonder. Monticello's design, history and legacy provide us with insight into the mind of a U.S. president.

Advertisement

Located in Albemarle County, just two miles outside of Charlottesville, Virginia, Monticello brings a sense of Old World grandeur to the American South. Jefferson didn't have an architectural mentor -- he was self-taught by European masters' drawings and essays on structural design. If we think of Jefferson as an artist, we can consider Monticello his self-portrait. The house reflects his ideas about order and style as well as family, lifestyle and certain political truths.

That's the allure of Monticello. Today, thousands of tourists visit the house each year, just like scholarly pilgrims who flocked to Monticello during Jefferson's lifetime. Those pilgrims hoped to catch a glimpse of the president -- even better, pick his brain about politics and philosophy.

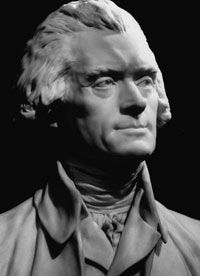

But the relics of the space in which he lived, entertained and planned his designs and curriculum for an American university draw people in for other reasons, too. They want to discover something about the inner life of a complicated man. Jefferson wrote about independence, but he had nearly 200 slaves. And despite his leadership of a young nation, he couldn't control even his own finances. Ultimately, an examination of the house is like looking at Jefferson with the humanizing perspective of today's media.

In this article, we'll learn how Monticello reflects Jefferson's tastes and attitudes. We'll also examine some of the innovations of the house. We'll discuss the lives of slaves at Monticello, and, we'll work toward a better understanding of the enigmatic president.

Advertisement