It's the columns that get you, endless rust-colored steel columns hanging from a ceiling. Each represents a county in the U.S. where someone (or several someones) was lynched. The Wilcox County, Alabama, column shows four people lynched between 1893 and 1904. The Avery County, North Carolina, column shows one. Counties from all over the South are represented, as well as a few in the West and Midwest.

It's all part of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, founded by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). The organization represents indigent prisoners and defendants throughout the state of Alabama, many of whom are, or were, on death row. The EJI's executive director and founder is Bryan Stevenson, whose bestselling memoir "Just Mercy" was recently made into a movie. Stevenson led the creation of the memorial and its sister site, the Legacy Museum.

Advertisement

The stereotype of lynching is a group of white men stringing up a black man from a tree. In truth, people were also shot, forced to jump off bridges or dragged behind cars. Sometimes thousands watched the murder in a carnival atmosphere. Postcards of lynchings were sold to spectators and body parts of the victims were even sometimes distributed as souvenirs. The EJI documented more than 4,400 lynchings between 1877 and 1950, 800 more than had been previously believed. (Lynchings declined in the U.S. with the end of legal segregation and the rise of the civil rights movement.) Most victims were African American men but women, poor whites, Hispanics and Asians were sometimes lynched as well.

While lynching had been practiced during slavery, it really got going during the Reconstruction era, after the abolition of slavery when African Americans started to make modest gains politically and economically. Lynchings were used to intimidate blacks and prevent them from asserting their rights.

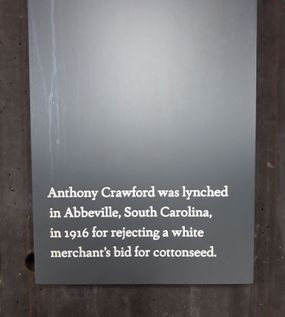

And what "crimes" were the people who were lynched guilty of? The memorial lists several on a wall, each with its own plaque. "General Lee was lynched in Reevesville, South Carolina, in 1904 for knocking on a white woman's front door," reads one. "Anthony Crawford was lynched in Abbeville, South Carolina, in 1916 for rejecting a white merchant's bid for cottonseed," says another.

Gabrielle Daniels, a program manager at the EJI, told an audience at the memorial last month that the idea for the museum developed out of reports the institute put out on slavery in 2013 and lynching in 2015. The memorial and museum were a chance to make those reports tangible.

"We found that communities didn't have a strong understanding of that history of terror and what that meant, to have a tool of racial terror to enforce segregation and economic exploitation," she said. "And what we wanted to do was think about how does a lack of public memory around over 4,400 victims of racial terror and lynching – what does that mean for us? What more have we lost other than just remembering someone's name? Have we lost a very important part of our context to piece together why we still need healing today?"

Another way to heal? Collecting soil. Inside the memorial are hundreds of jars of soils from the sites of these lynchings that were collected by victims' families or community volunteers. In the park surrounding the memorial are duplicates of the steel columns waiting to be sent to the counties where the lynchings were carried out for community remembrance projects, provided the requesters have shown efforts to build community and address inequities.

Advertisement