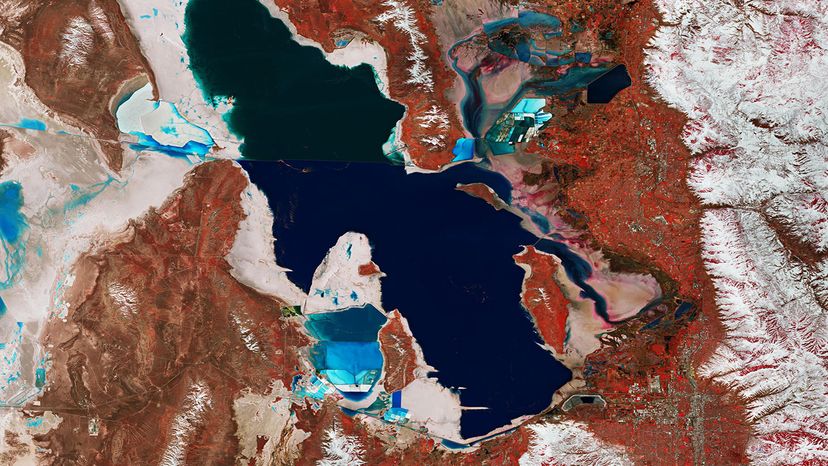

In the hot summer of 2021, one of America's most spectacular lakes has been in the news and the reason for that is not good.

Salt Lake City, Utah, is just a short road trip away from its natural namesake, a large body of water known as the Great Salt Lake, or the "GSL." Filled with around 4.5 to 4.9 billion tons (4 to 4.4 billion metric tons) of dissolved salt, the lake has certain areas that are roughly 10 times saltier than the ocean.

Advertisement

Utah residents have gotten used to the GSL's inconsistent size.

It's always shallow, that much is a given. Throughout recorded history, no part of the Great Salt Lake has exceeded 44.6 feet (13.6 meters) in depth. Summer heat takes its toll; the water is typically 1 to 2 feet (0.3 to 0.6 meters) higher in May, June and July than it is in the fall and early winter.

Some years are gentler than others. At its maximum recorded size, the Great Salt Lake expanded to cover an area of over 2,300 square miles (5,956 square kilometers), making it bigger than the U.S. state of Delaware.

We are currently witnessing extremes in the opposite direction. Right now, the GSL is shrinking.

Scientists keep tabs on the lake's fluctuating surface elevation. On Tuesday, July 20, 2021, this fell to just 4,191.4 feet (1,277.5 meters) above sea level, tying the lowest GSL surface elevation ever recorded.

And that wasn't the end of it. Over the following weekend, the United States Geological Survey announced that the water level in the southern part of the lake had dropped even lower, a worrying development for conservationists.

Advertisement